We caught up with PhD scientist and Ambassador Lindsey Dougherty to get you the the where and how to capture this interesting nurturing behavior.

Where are the best places to find yellowhead jawfish?

Yellowhead jawfish (Opistognathus aurifrons) are common in the Caribbean. I have seen them in Bonaire, Curacao, and Little Cayman. There are other species of jawfish that also have egg-carrying males such as the Indo-Pacific yellowbarred jawfish (Opistognathus randalli) that I’ve seen in Wakatobi and the banded jawfish (Opistognathus macrognathus) which I’ve seen at the Blue Heron Bridge in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

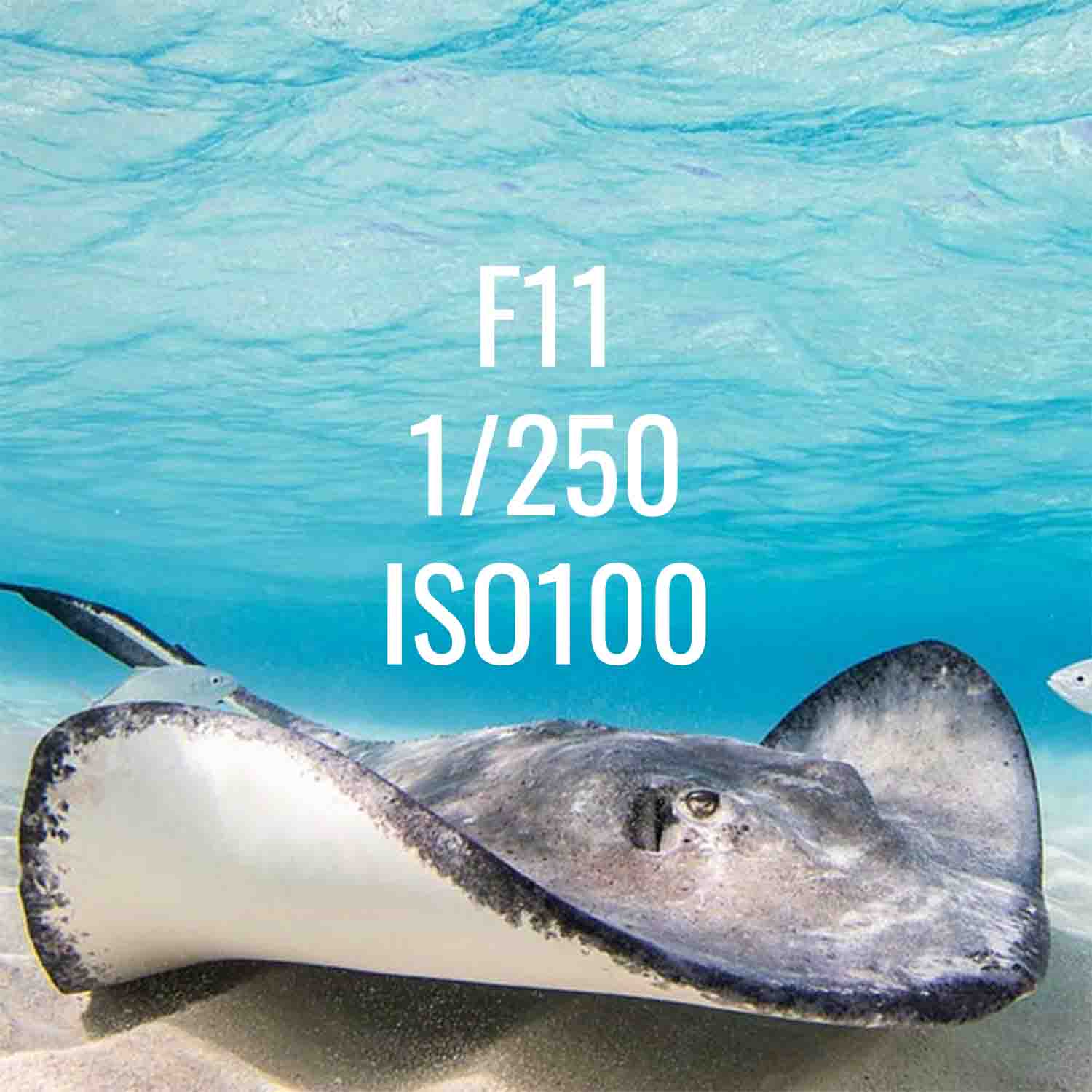

There are two environments in which I look for jawfish; the first are sand flats between the shallow reef and the reef wall. In Little Cayman, this is an excellent area to find jawfish, along with southern stingrays, pipefish, flounder, and garden eels. On our last trip, I actually watched a hogfish eat a garden eel, which was something I hadn’t seen before. I could tell he was hunting based on his posture (downward facing) and stillness, so I stayed with him for a few minutes and the next thing I knew, the garden eel was gobbled up in a cloud of sand.

The jawfish in this area burrow in sand, so that is your first clue as to their whereabouts. They often line the rim of their burrow with small rocks or coral pieces, so that is another clue that it may be a jawfish hole (and not a worm hole). Some crustaceans do this also, so it’s not a sure bet, but it’s a start.

When you do find one jawfish, there are always others around, so search the surrounding area for one with eggs.

The second environment in which I look for them (in the absence of a sandy flat) are sand pockets on sloping reefs. Jawfish are territorial, so there will be a clearing at least a foot or so around their burrow. Once you find a sand pocket, look for holes 1” or so across, surrounded by rocks or coral. Jawfish usually don’t retreat all the way into their burrow, so you can get close to see if any of them have eggs. If not, keep hunting!

What’s your technique for approach?

Jawfish are very wary of divers – they can see both your shadow and your movement. Avoid swimming over them and instead approach from the side. Stay very low to the substrate (without touching it) and move forward as slowly as possible.

To get the shot of the eggs, there was a point at which the jawfish would not let me get any closer without retreating into its burrow, so instead I turned on my LCD screen and moved the camera alone close enough to the burrow to get the shot.

A diopter would be another good tool for this type of photo. In my dream world, I’d have a rebreather so that my bubbles wouldn’t frighten any of the animals I photograph! Overall, the key is patience, as once the jawfish is comfortable, he will allow you to get quite close. It’s a good chance to practice your buoyancy and breathing.

What lens and camera settings are you using?

To shoot jawfish, I use the Canon EF 100mm f/2.8L Macro IS USM Lens with the Ikelite flat port. For macro photography in general, I shoot in manual with jump settings of ISO 100, 1/200s, and I dial up the f-stop as much as needed.

Changing your aperture also changes your depth of field. The smaller the aperture (larger f/number), the greater the depth of field. Apertures of f/11 to f/22 or even smaller are often required to get enough of a macro shot in focus.

In the shot of the jawfish eggs, I wanted it to be a little more artistic so I went with a lower f-stop to try and pinpoint focus just on the mouth. Usually there is good natural light in the sandy areas in which you find the jawfish, so you can go with a faster shutter speed since the animals move their heads around quite fast.

What are you using for lighting?

I use Ikelite DS51 dual strobes with TTL, although the jawfish in these photos was so shallow that the flash wasn’t necessary with the sun out.

As divers we should always be wary of how many times we are using strobes on small creatures, as the light can be harmful to their health. Good guidelines, developed by Dr. Richard Smith for pygmy seahorses, suggest no more than 5 flash photos and to avoid lights if possible. In some cases, a red light can be useful to focus photo subjects, as many marine creatures are not photosensitive to red light (red light attenuates very quickly in the ocean). I have two lights on my rig which I use to look for creatures in small cracks and crevices.

Once I find them, I turn off my lights to avoid causing the animals to retreat deeper into their shelter. If you do accidentally cause them to retreat, you can wait with your lights off for them to re-emerge (if you have time, air, and a patient buddy). TTL settings on strobes will help determine how much light you need for the critters in tough or dark places.

How do you get “the shot”?

First, you have to be lucky enough to find a male jawfish with eggs. I have gone entire trips without finding one – don’t be discouraged. Always keep your eyes peeled, and if you find any jawfish, look around because there are always more nearby! Next, you have to have the air (and the buddy) that allow you the patience to let the jawfish acclimate to your presence.

If you know you’re headed to a spot where there are potential jawfish, let your buddy and the divemaster know that you’re hoping to get a photo of eggs and may hang back a few minutes.

Finally, watch the jawfish and wait for the position you want him in. Jawfish are wary of their surroundings and are constantly changing their lookout position, so there are plenty of chances to get your ideal setup. Before shooting, and as you move closer and closer, take a minute to watch the animal (not through your lens) to understand and appreciate their behavior, then anticipate the shot. Patience is key!

Have you been able to catch the eggs hatching?

I haven’t been lucky enough to catch the eggs hatching, but that would be quite amazing! Depending on the species, some jawfish can mouthbrood eggs for up to a week, so if you have the time, it would be great to go back and visit the same fish every day to document the egg growth and hope for the ultimate hatching shot!

Want to know more about mouth brooding jawfish? Check out Lindsey's article for Scientific American.