This fuzzy American Dagger Moth showed up one day on our smoked-glass table and reminded us of a few nudibranchs we have seen. The black background of the table provided a nice dark backdrop. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

By Glenn Ostle

Even if you can’t get in the water, you can still work on perfecting your macro shooting. The world is full of tiny critters ready for their “closeup.”

Bees are fascinating subjects and especially photogenic when they land on colorful flowers. This head-on shot of one with its head speckled in pollen, captured while hand holding the camera, is one of our favorites. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Before taking up underwater photography twenty-five years ago, I didn’t pay much attention to all the miniature life just below my fins. The ocean was too big and beautiful to concern myself with the small stuff. But, after getting my first underwater camera (a Nikonos V with framers, for you older shooters), I soon became enamored of the incredible diversity of tiny underwater life and how, with some attention to settings, lighting and composition, it could be showcased in photographically stunning images.

This creepy-crawler was almost impossible to see with the naked eye as it crawled across our smoked-glass table. When we enlarged it, we were surprised by its lobster-like appearance and pincers. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Today, being stuck at home with fewer opportunities to travel and dive, I’ve looked for ways to stay sharp with my camera, and especially maintain my “macro eye.” Encouraged by Steve Miller’s innovative work in his backyard, I began to look around closer to home and discovered that there are just as many tiny critters available to photograph on land as there are underwater -- and often just outside our back door.

This long-legged grasshopper was moving from stalk to stalk on a Gladiola plant, looking like something out of a Tim Burton movie. Once again, this was taken by hand holding the camera and using continuous mode and a fast frame rate. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Underwater macro photography is incredibly challenging as it combines diving skills with photographic techniques. An underwater photographer has to be able to focus on the tiniest subjects while still being aware of depth, bottom time, air consumption, buoyancy and his buddy’s location.

This interesting scene unfolded one morning on our deck umbrella. The fly was thoroughly engrossed in consuming what was left of a dead spider and as a result let me get very close with my camera. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Land photography is certainly easier, but it shares a number of similarities with underwater photography. For instance, photographing a bee buzzing around a flower is similar to trying to capture a clownfish darting in and around an anemone or colorful soft corals. Trying to pull sharp focus on a tiny jumping spider is much like trying to focus on the eyes of a shrimp tiptoeing across a corallimorph. Spiders are like land-based crabs, butterflies are airborne versions of reef fish, and there’s a world of detail to discover in a dragonfly’s wings. We recently photographed a fly feasting on a dead spider which is sort of disgusting but is very reminiscent of the life and death encounters that occur daily underwater.

This unusual specimen was a real surprise. When we enlarged the image, we thought it looked like a dragonfly with brush bristles for a head. Another example of how land-based creatures can be as unusual as their underwater cousins. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

It is currently summertime here in North Carolina, so there’s lots of life abound. Bees go about their task of collecting pollen while taking very little notice of a hulking giant with a camera looming over them. I’ve found all manner of tiny subjects perched on just about everything that grows; some so tiny you need a magnifying glass to see them clearly.

While photographing flowers, we came across a pair of Japanese Beetles actively engaged in perpetuating the species. We particularly like the colorful setting which is a great benefit that comes from shooting among flowers. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

On our back deck we have furniture that includes a table with a smoked glass top which appears almost black. While sitting there waiting out the COVID19 crisis, a myriad of tiny organisms have landed, walked across or somehow just shown up on that table. I suspect many of them -- which my partner Pam and I now refer to as our “COVID Critters” -- mistake the dark black surface for a convenient pond. Photos of these table visitors that show them posed against a dark black background are reminiscent of pictures we’ve taken on blackwater dives. Because of this, we now jokingly refer to this type of photography as “blacktable diving.”

Spiders are like the land version of crabs, but with more eyes. Photographing a jumping spider can be a challenge as they can…jump, often and unexpectedly. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Here are my top 5 rules-of-thumb and techniques I’ve compiled regarding land-locked macro dives:

1 | Have the right equipment.

I’ve been using my Nikon Z6 with an AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/2.8G macro lens in concert with a Kenko 1.4 teleconverter. For light, I’ve used both a front mounted Nikon ring flash as well as a Weefine 1000 continuous light designed for underwater photography. The ring flash helps keep ISOs, and thus noise, to a minimum, and the Weefine, which I’ve adapted to fit on the front of my 105 lens, provides a nice, balanced fill light for some shots.

This long-legged insect landed on our table one day. The black background provided by our smoked-glass table, added a nice reflection that added to the photo. Again, reminiscent of some of our photos from our blackwater dives. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

2 | Increase your depth of field.

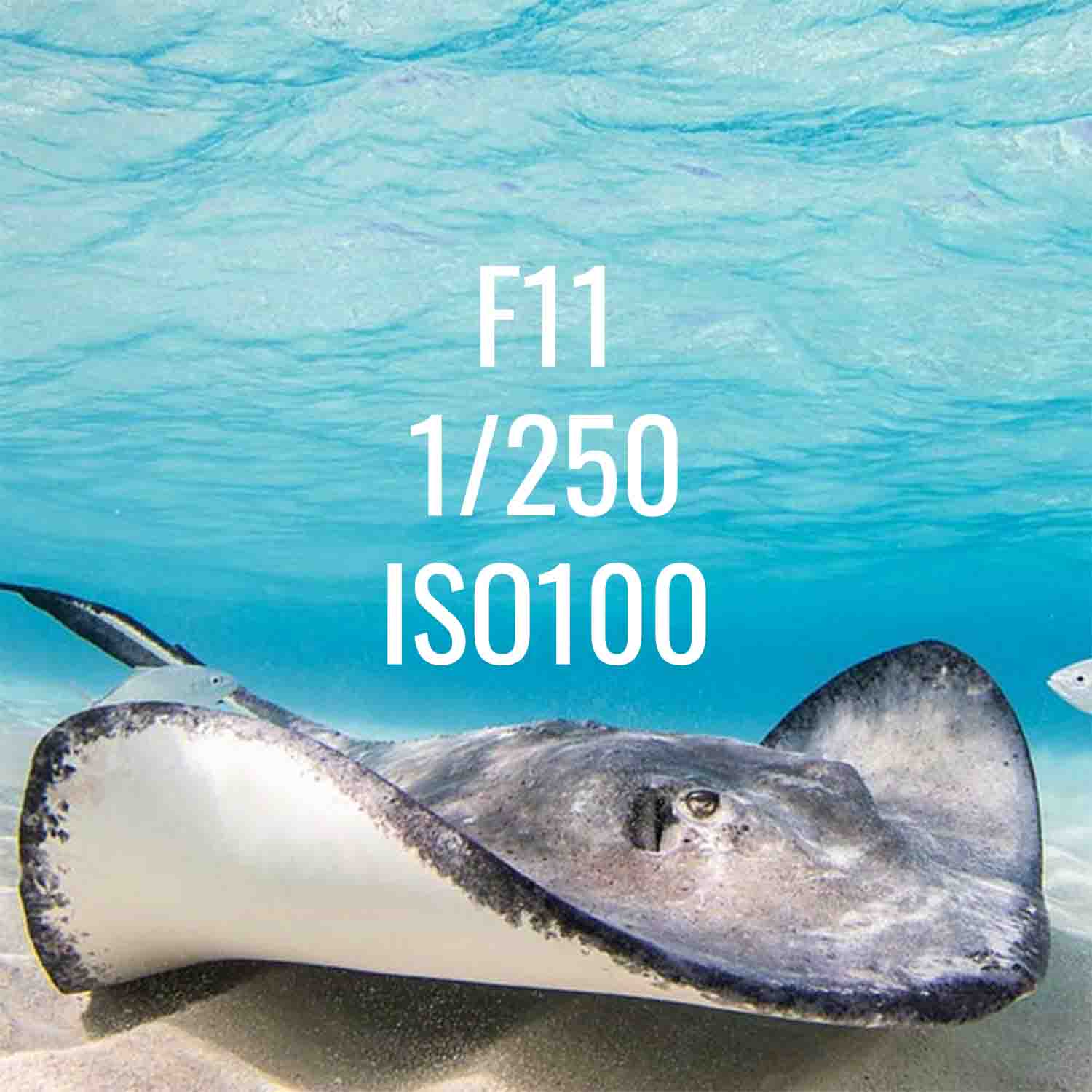

As in underwater photography, small apertures are needed to maximize depth of field. I’ve shot with f-stops ranging from f16 to f51. Of course, this depends on the light (the more the better for these small apertures).

3 | Use Auto ISO to your advantage.

This jumping spider was an exceptionally small. Trying to photograph him against the dark table was a challenge. However, the reward was a nice composition with a reflection. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

4 | Get used to hand-holding.

A tripod can be extremely helpful at times but often becomes just an impediment to being able to move around quickly and follow the action of jumping and flying subjects. When hand-holding my camera with a continuous light, I often use auto focus with high continuous release mode, to fire off up to a dozen frames per second in order to capture at least one in-focus shot among the many out-of-focus ones. One great shot will make my day!

5 | Get creative.

This yellow creature attached itself to our glass back door one evening. I photographed it from the opposite side of the door, using a continuous light source to reveal the details in its wings. Photo © 2020 Glenn Ostle

Practicing on land can help perfect some of the techniques you will need the next time you take the plunge, and in doing so help maintain your “macro eye.” And best of all you don’t have to worry about running out of air, exceeding bottom time, or losing the boat. When Pam and I are finished shooting in the backyard, we find our way home by simply turning left at the azalea bush.

Ambassador Glenn Ostle combines his photography skills with a writing ability honed through more than 30 years working in marketing and publishing including 10 years as Editorial Director of a major trade publication. He is a long-time member of the Nikon Professional Society and for years has contributed articles to a number of dive and travel magazines. Check out more of Glenn’s COVID critters as well as all manner of wildlife from both above and underwater on his website featherandfins.smugmug.com.

Ambassador Glenn Ostle combines his photography skills with a writing ability honed through more than 30 years working in marketing and publishing including 10 years as Editorial Director of a major trade publication. He is a long-time member of the Nikon Professional Society and for years has contributed articles to a number of dive and travel magazines. Check out more of Glenn’s COVID critters as well as all manner of wildlife from both above and underwater on his website featherandfins.smugmug.com.

Additional Reading

COVID-19 Check-In | Ambassadors, Part 1

An Insider's Guide to Blackwater Photography

Dive Diversions: On Safari in Uganda with the Sony Alpha A7R III