By Steve Miller

Aperture is one of the three major camera-set variables that affects your image's exposure. Along with shutter speed and ISO, aperture affects the amount of light that reaches the camera's imaging sensor.

Think of the aperture like a pinhole. As the hole gets larger more light gets through. It's the same with your aperture.

The lens opening reduces to half its size with each change in f/stop. Larger f/stop numbers let in less light, typically requiring more artificial light (strobe power). Image © KoeppiK / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) (modified text)

Aperture is represented by an f/number. Each change of f/number is called an f/stop or just stop. The only confusing bit is that a small f/number is a large aperture, and vice versa. When we say "large," "wide," or "wide open" aperture, we're referring to the range from f/4 to f/6.3. When we say "small" or "narrow" aperture we're usually talking about f/8 (small) up to f/22 (smaller) or even f/32 (smallest).

Each lens has a maximum aperture value or value range. The maximum aperture your lens offers determines how bright your scene appears to both your eye and your sensor- thus affecting how easily the autofocus does it’s job. We often call this how "fast" a lens is.

A lens that is f/1.2 can be triple the price of a "slower" f/4 lens in the same focal range. Even when shooting at smaller apertures the maximum aperture still affects the cameras performance - and your ability to see the image - since the lens only "stops down" a split second before capture. Topside photographers rarely have issue achieving a focus lock quickly. Underwater the lack of overall contrast and light (the keys to fast autofocus) can cause your camera to struggle when focusing.

(Left) A landscape shot at an aperture of f/11 has a deep depth of field where the foreground and background are all in focus. (Right) A shot of a turtle with very shallow depth of field shot wide open at f/4.5.

The most significant effect of aperture is brightness but it also affects depth of field. Depth of field refers to how much of your image's foreground and background is in focus. A very large aperture like f/2.8 will produce a shallow depth of field. You may be most familiar with this effect in portraits where a person's face is in focus but the background behind them is blurry. Small apertures will have deeper depths of field. Imagine a landscape where rivers, trees, and mountains are all in focus.

Small apertures improve photo sharpness in two ways: by increasing depth of field and by reducing aberrations. Photos taken at smaller apertures (higher f/numbers) will be sharper than photos taken at larger apertures. Depending on the distance to subject, lens, and conditions, the effect may be more or less noticeable.

When to Change Aperture

If you are using a camera with manual settings for the first time, you are finding a very wide range of options for aperture, shutter speed, and ISO compared to cameras that only work in automatic modes.

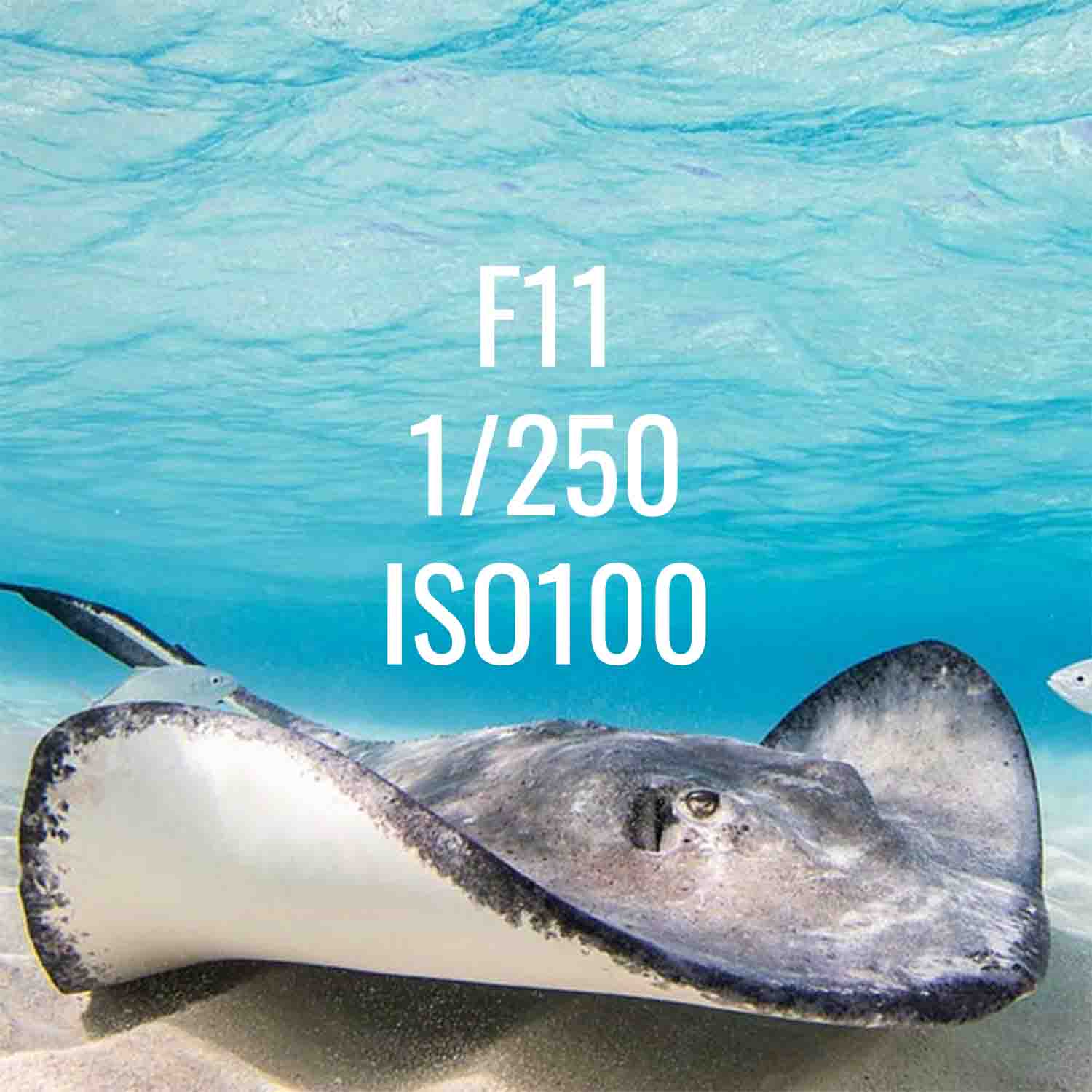

Apertures of f/8 and up provide excellent depth of field - and edge sharpness - when shooting a wide angle or zoom lens underwater. The smaller your aperture, the sharper the edges of your photos will be. Photo © 2020 Steve Miller

Close Focus Wide Angle (CFWA)

Conventional wisdom for choosing aperture for a close focus wide angle (CFWA) image is to start by setting the aperture based on your depth of field needs. An aperture value of f/8 is typically a good starting point. Significantly smaller apertures of f/18 to f/20 makes for a brilliant (if slightly underexposed) background when shooting at an extreme upward angle. The best way to select the right value is waste a frame and preview the image. The preview and histogram may be more helpful than the camera's light meter, which tends to make all of your images look very bright. Pick an ISO to match the ambient light in the scene (the more light you have, the lower the ISO). Then bracket your shutter speed until the water in the background is the brightness you like, from black to bright blue.

If you're shooting TTL strobes, there's an alternative that may make you faster on the draw. First, set your ISO to match the brightness of the scene (typically low, for example in the 200 range for tropical waters). Then set your shutter between 1/125 to 1/200 (the ideal compromise to eliminate motion blur and allow flash synchronization). Then shoot several images bracketing your aperture.

So can any aperture work? Yes... if it's balanced with the ISO and shutter speed. If you are using an upward camera angle in clear water you will probably end up with an aperture in the f/8 to f/11 range.

What to focus on? An aperture of f/13 is very forgiving as you move away from the lens. Focus on the subject that is closest to you! Photo © 2020 Steve Miller

CFWA and Depth of Field

The above scenario has worked great for me for years, but it is predicated on the idea that you are using a super wide angle lens- or even better, a fisheye. Super wide angle lenses share a wonderful attribute: they have incredible depth of field inherently built in to the optics. Once your focus locks and you make your capture, the subject and everything farther away from that point will be sharp. However, anything closer than the focus point will be softer. This may be the case at any aperture value depending on your distance to the subject.

Smaller apertures (larger f/numbers) are highly desirable for improved edge sharpness when shooting CFWA and reefscapes. So once you have balanced the background water color properly, aim for an aperture of f/8 or smaller whenever you can.

A small aperture is critical when shooting super macro, like with this tiny pygmy seahorse. Your depth of field is only millimeters when working at close distances with a long macro lens in the 90-100mm range. Photo © 2020 Steve Miller

Macro Photography

When we move to longer focal lengths (and in our case mostly we are talking about macro lenses) the depth of field can become razor thin. Small apertures are your friend here. When the surge is rocking you back and forth and you are trying to lock focus on the eye of a tiny subject, misses are common. Many beautiful macro images miss the perfect focus point by a millimeter and the softness makes the image suffer.

Think of f/8 as a minimum when shooting macro underwater. If you're shooting a DSLR or mirrorless camera with dual strobes, then aim for the f/16 to f/22 range. Focus on the eye of your subject and bracket the aperture to acheive the perfect bokeh effect (that dreamy softness separating your subject from the background).

Just how shallow is depth of field at larger apertures? This photo was taken at f/3.2 and only one of the frog's eyes is perfectly in focus. But that doesn't have to be a bad thing- some macro shots are all about a single point of spot focus. Photo © 2020 Steve Miller

Aperture Priority Mode

If you're shooting a compact camera without a full manual (M) camera mode, then Aperture Priority (A or Av) mode can be your friend. It's important to keep an eye on the shutter speeds the camera selects. It may start shooting at too slow of a speed, leaving you with a card full of motion blur. Check whether the camera's menu options allow you to set a minimum shutter speed when shooting in Aperture Priority.

Most compact point-and-shoot cameras benefit underwater from turning on the macro focus mode, even when shooting wide angle. This mode typically forces the camera to shoot at smaller apertures resulting in an image with better color balance, especially when shooting with strobes.

Aperture priority mode set to f/8 with TTL strobes allows you to capture a wide scene in focus with a compact point-and-shoot camera and fisheye lens. This image was shot with the Olympus Tough TG-6 and FCON-T02 fisheye lens. Photo © 2020 Steve Miller

Conclusion

Aperture value is tremendously important to the exposure and sharpness of your underwater photos. Understanding aperture will take your photos from average to awesome! Remember that large numbers mean small apertures. As a general rule of thumb, start small and go from there.

Related Article: When to Change Shutter Speed Underwater

Related Article: When to Change ISO Underwater

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Additional Reading

Super Macro Underwater Photography Techniques

Close Focus Wide Angle In Depth

How to Shoot Split Shots (Half-In, Half-Out of the Water)

Why You Need a Fisheye Lens Underwater

The Myth of TTL Strobe Exposure Underwater

Straight vs 45 Degree Magnified Viewfinder for Underwater Shooting