By Steve Miller

Shutter speed is one arm of the trifecta of important settings for proper exposure; the other two being aperture and ISO. It can range from many seconds to a tiny fraction of a second.

The Magic Numbers

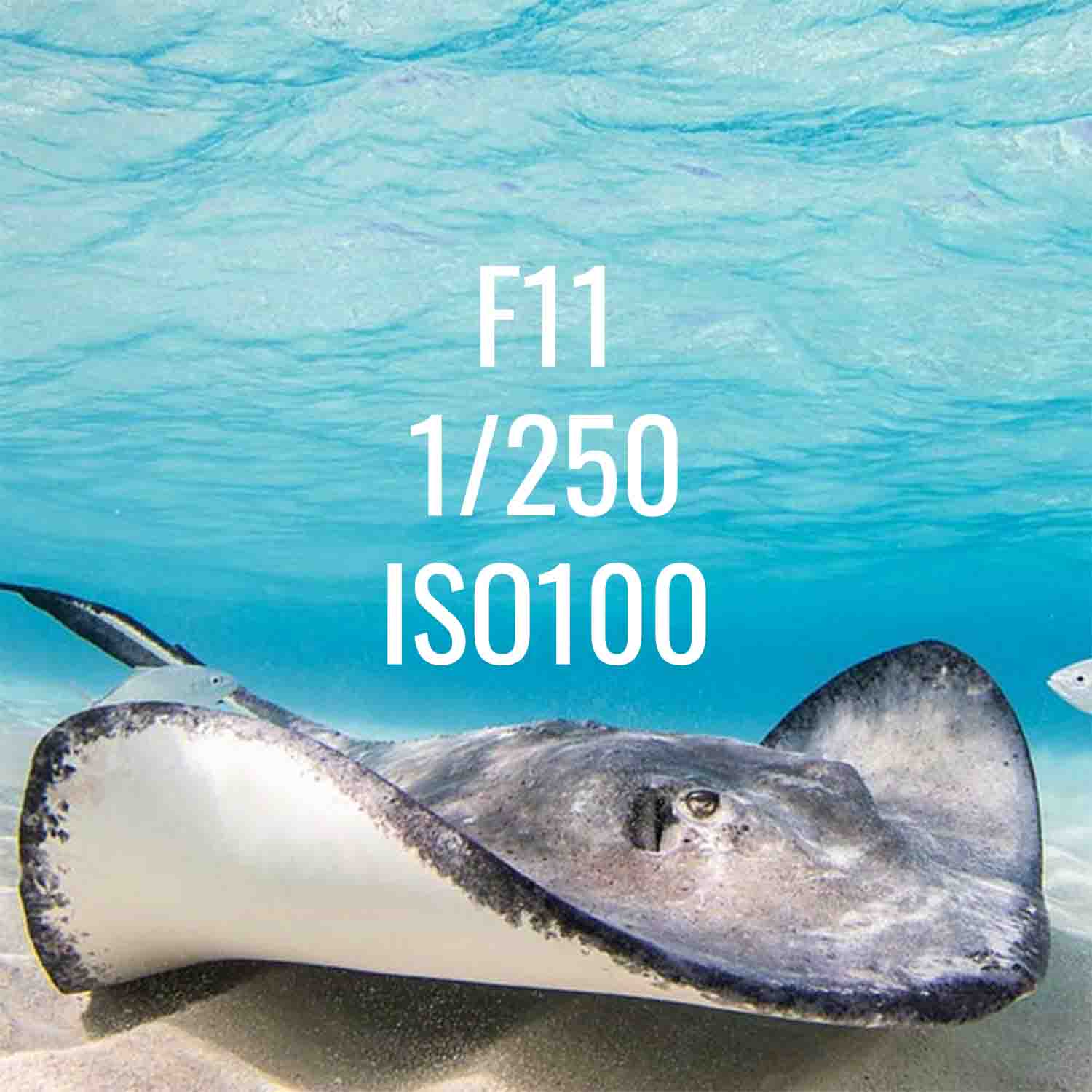

The metadata from thousands of published images shows that shutter speeds of 1/125 to 1/160th of a second work well about 90% of the time underwater. These speeds are fast enough to prevent motion blur from camera movement, as well as the movements of most animals that are in a relaxed state.

A shutter speed of 1/160th second is fast enough to stop the motion of whalesharks and most big animals when they aren't in a hurry.

The range we're typically using for hand-held photography is 1/60th of a second and faster. Each time you go to the next faster setting (1/60 to 1/125, 1/125 to 1/250, and so forth) you lose one stop of light. In wide angle photography shutter speed has a pronounced effect on the color of your water column. Generally speaking, faster shutter speeds will make the water column look more richly colored and slower shutter speeds will make it look lighter.

Cruising sharks can be captured at shutter speed of 1/125. The flash will also freeze them when they are in range- figure around 4 feet with two strobes and clear water.

Typically I start with 1/160 and leave it at that setting until I need extra reach in my aperture range.

The Other 10%

Shutter speed is you best tool for creating a sense of movement. It can also bring a softness to make an image just feel different and easier to take in compared to the riot of color and texture we often capture (assuming you're shooting with strobes).

Twilight photography with strobes. Nothing freezes motion as effectively as a flash. TTL strobe flash durations can be as short as 10,000th of a second, fast enough to eliminate motion blur with even the fastest subjects.

Fast Shutter Speeds

There are certain situations where you will need to change the shutter, particularly shooting natural light (without strobes). Strobes provide a quick burst of light - only a fraction of the time that the camera is actually capturing the image. This helps to freeze motion of moving subjects.

The water line always moves with over-under photography- even in calm waters. (left) A faster shutter speed will freeze the water for a more crisp waterline. (right) The water line doesn't necessarily need to be sharp for a pleasing split shot.

Strobe light is quickly absorbed by the water column, so they become useless when shooting larger animals that are swimming more than about an arm's reach away. Your best option is typically to turn your strobes off and shoot natural light. In these conditions, fast swimming animals like dolphins will blur if you use your standard "reef settings" of 1/125 to 1/160. We recommend at least 1/500th second (or faster!) for swimming dolphins, or feeding sharks.

These faster shutter speeds will also keep the water line on your over-under photos (where the frame is half-in, half-out of the water) sharp. A slower shutter speed will make it look more like the sky is melting into the sea.

In low light, slowing the shutter is one of your three solutions in-camera. Cenote light is so clean, that even 1/60th second leaves well defined light rays- the rays don't move as much as the surface is calm. Unless you hold very still 1/25th second can produce motion blur without a tripod. Dancing light rays will go soft and creamy since they are moving.

If you are trying to capture dramatic light rays, the faster the shutter, the more defined they will be. When shooting in dark environments like cenotes and caverns, it will be a balancing act between ISO and shutter speed to get defined environments and sharp light rays without too much graininess or blur.

Some light rays are better than others. 1/125th second or even slower will still image high quality light rays. To get the best rays you want clear water and something to block most of the light. The Rays form best spilling over the side from a dark area.

(left) A slow shutter of 1/13th second will definitely create motion blur. -Except for what is "stopped" by the flash. To do this spin twist the camera around like opening a hatch, then reverse it for smoothness depressing the shutter half way through the spin. (right) 1/8th second spin creates more blur as you move from the middle. Round subjects and round lenses lend themselves to the shapes you are creating.

Slow Shutter Speeds

Motion blur can be created intentionally for artistic effect. We can pan a subject to blur the background, and even incorporate flash to capture both the blurry, creamy motion and the crisp sharp lines that the flash defines. A good rule of thumb is to expect some motion blur somewhere if you try to hand hold a shutter of 1/30th second or slower- although Pro’s will do this often with scenic wide shots, with the tiny reef fish the only blur for artistic effect.

1/100th second is pretty fast for motion blur, so you have to spin the camera a little faster.

Shutter Priority

If the speed of your shutter (length of your exposure) is the most important thing, Shutter Priority (Tv) mode may offer you the best solution. Shooting whalesharks in natural light is a good example. You want to set your ISO as low as possible for sharpness, and you would like a small aperture to increase depth of field (the range of distances at which objects will be in focus). Most importantly, if you shoot too slow, the animals will be blurred.

Since wide angle lenses have amazing depth of field, you can set your shutter to 1/160, and let the camera select the aperture as you capture images with the sun in different positions. This will allow you to follow the animal as it moves through the scene (and different exposures) without making any changes. You can concentrate exclusively on your composition. The same thing works well with dolphins, just at a much higher speed of 1/540 and above.

You can use shutter priority with flash, but the manual (M) camera mode this is preferred. You may find Shutter priority wants to brighten your background too much, making the water column look a washed out teal color.

1/640th second helps stop dolphin that are swimming quickly- too far away for the flash to help. It is easier to swim quickly without strobes on your setup, if these are what you are going for. These dolphin are wild and on the move- although they will pass close to you, the speeds can make "shooting from the hip" the best approach... just point and shoot!

Flash Sync Speeds

Depending on your camera, it may also be the required speed to synchronize properly with your flash… it certainly has been for many years. Most Canon and Nikon DSLR cameras have a maximum flash synchronization speed of 1/200. Some Sony and Olympus mirrorless cameras sync up to 1/250. Trying to shoot faster than these speeds with an external flash attached will produce an image with a black band on the right-hand side.

Some cameras feature high speed synchronization (HSS) or focal plane (FP) flash, allowing you to fire an external flash at faster shutter speeds. These modes are effectively useless underwater because they so severely limit the flash output.

Conclusion

It's important to understand shutter speed if you're shooting in manual camera mode underwater (as you should be, most of the time). But don't over-think it. For macro, a good rule of them is to set it around 1/125 and adjust your aperture as necessary. For wide angle reef-scapes, start at the same place and take a couple of sample shots. Go faster if it's bright out and you want the background water to be a deeper blue (or green) color.

Related Article: When to Change ISO Underwater

All photos Copyright © 2020 Steve Miller

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Ambassador Steve Miller has been a passionate teacher of underwater photography since 1980. In addition to creating aspirational photos as an ambassador, he leads the Ikelite Photo School, conducts equipment testing, contributes content and photography, represents us at dive shows and events, provides one-on-one photo advice to customers, and participates in product research and development. Steve also works as a Guest Experience Manager for the Wakatobi Dive Resort in Indonesia. In his "free" time he busies himself tweaking his very own Backyard Underwater Photo Studio which he's built for testing equipment and techniques. Read more...

Additional Reading

Why You Need Strobes Underwater

4 Creative Uses for Backscatter in Underwater Images

How to Shoot Split Shots (Half-In, Half-Out of the Water)

Techniques for Photographing Sharks

Tropical Reef Underwater Camera Settings