By Ambassador Lindsey Dougherty

Jimmy Fallon was awarded a golden retriever puppy during a “pup quiz” with Gisele on his late night show when he correctly answered the question; “Which of the following is not a real sea creature?” The choices were A) Disco Clam, B) Shimmying Clownfish, or C) Musical Furry Lobster. (The answer is B, but I was over the moon that the disco clam’s 15 minutes of fame had finally cracked the late night circuit).

Let’s back up - you may be wondering who am I and why I follow the press for updates and google alerts on the ‘disco’ clam. You may also be wondering what on earth a disco clam (also called an electric scallop) is. Well - the disco clam is a bright red, coral reef-dwelling, long-tentacled bivalve that flashes. Yes, it actually flashes. I know this, as the disco clam was the subject of my PhD and post-doctoral research and I spent seven years diving with them throughout Indonesia, Australia, and Palau. I am actually the world’s foremost expert on the disco clam (even though it’s technically by default, since I’m the only person who studies them).

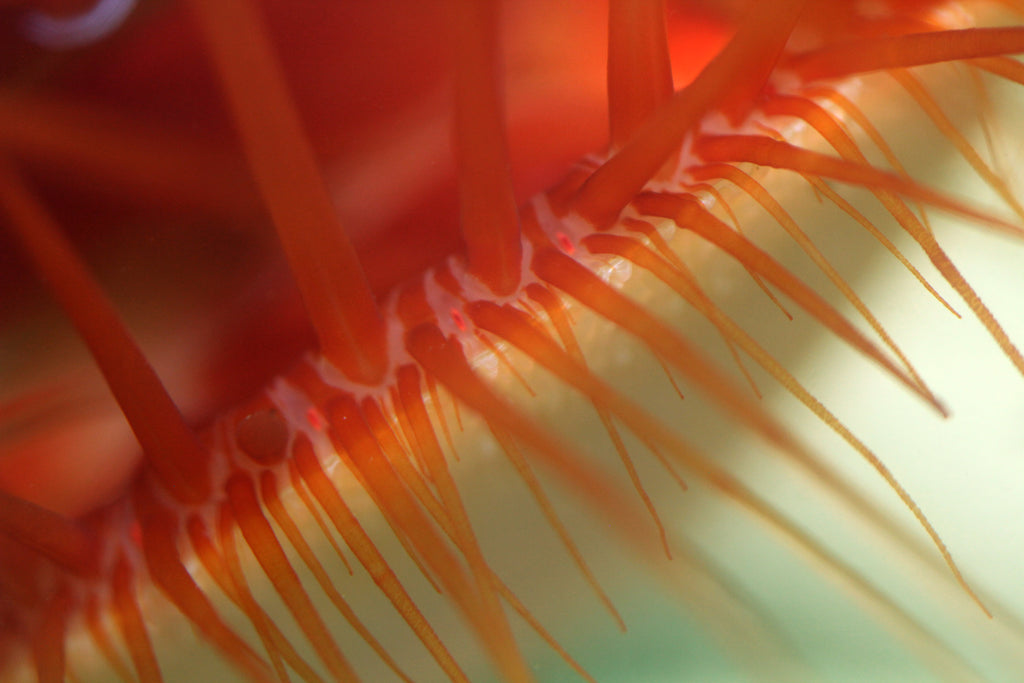

Canon EOS 60D with Canon 60mm lens • A macro shot from the lab showing the reflective portion of the mantle of the disco clam.

I first saw a disco clam while diving in Wakatobi, Indonesia in 2010. I was doing an independent undergraduate research project in the world’s best muck at Lembeh Resort with their in-house marine biologist, Dimpy Jacobs, and ventured south to meet my family for some recreational diving. When our divemaster showed us the clam, we were mesmerized. I started taking photos (at the time, with my silver Sony Cybershot point-and-shoot digital camera, sans flash or lights - you’ve come a long way, baby). The divemaster gave me the video sign, so I also recorded some film. Afterwards, my sister and I reacted like any normal people would – by disco dancing underwater. We also may have written a song about the disco clam to the tune of “I will survive” later that evening (“At first I was so plain, was not electrified…”). All cards on the table, there might have been champagne involved.

Once I left Indonesia, I started investigating the disco clam further – it didn’t seem as though anyone actually knew how it flashed. This curiosity eventually led me to a PhD program in Dr. Roy Caldwell’s lab at the University of California, Berkeley. A 5-year PhD seemed like more than enough time to answer a couple seemingly simple questions:

How does the flashing work?

The flashing was originally thought to be bioluminescence – which is the chemical production of light. We often see bioluminescence while night diving (if you haven’t, try turning off your lights near the end of the dive and moving your hands or fins around - you can also sometimes spot it in the wake of a boat, of if you wave your hand near a large surface such as a barrel sponge - while being careful not to actually touch it, of course!)

The disco clam, however, is not producing bioluminescence. Bioluminescence simply isn’t bright enough to be seen during the day. Instead, the disco clam has specialized tissue along the edge of their mantle - one side is filled with silica nanospheres that are extremely good reflectors. If you think about it, the tissue is filled with teeny tiny disco balls! The other side doesn’t have any spheres, so it’s not reflective. The clam flips back and forth between the reflective side and the non-reflective side very quickly (~2Hz) which to our eyes, makes it appear as though it is flashing.

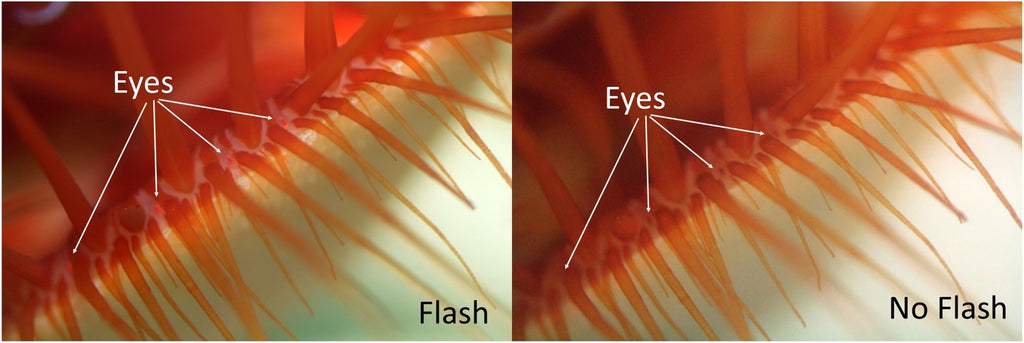

Most people don't realize that disco clams (or any clams) have eyes. Here you can see that the eyes are reflective. In the left shot, they return the light of the flash. Each disco clam has about 40 eyes on top and bottom, nestled in between their tentacles.

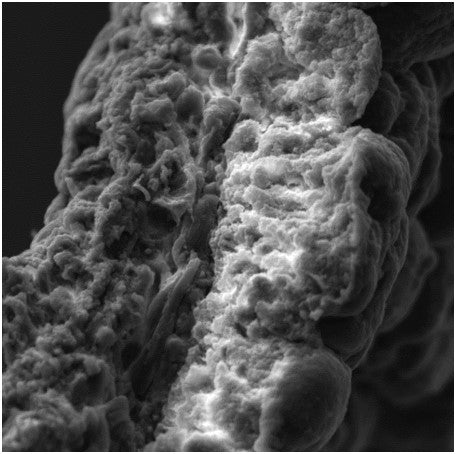

When I explain this to kids, I use a bright red scarf that has foil taped to one side. I have them line up holding it and do the wave like they’re at a football game; you see the shiny side, then the red side, then the shiny side, then the red side. I used transmission electron microscopy to see the tissue’s internal structure, high-speed video to confirm tissue movement and speed, energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy to reveal that the spheres on the reflective side were composed of silica, and optical modeling to show that the size of the silica spheres was nearly optimal for scattering blue light. Therefore, a modest mechanism involving two-sided tissue and rapid movement produces a remarkable effect that may function as an underwater signal.

This is a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the two-sided tissue that reflects in the disco clam mantle. The silica spheres that cause the reflection are too small to be seen here, so we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to get an even closer shot.

Why are they flashing?

The second question my research tackled was less simple than it appeared: why are the clams flashing? When an organism does something energetically costly, there is usually a function behind it. Our three hypotheses for the purpose of the flashing were that it acts to (1) attract other disco clams to settle nearby in order to mate, (2) to lure phototaxic plankton (prey attracted to light), or (3) to warn off predators. The problem with (1) is that even though the disco clams have up to 40 eyes, we found that they can’t see each other flashing. The problem with (2) was that the plankton that the clams eat are so small that they also can’t see the flashing, nor swim toward it very well (and, solid lights are better at attracting organisms than flashing ones).

What we do believe is that the bright red tissue acts as a warning signal (called aposematism), and the flashing augments that bright color to tell predators not to eat the clams. Bright colors in nature often signal toxic chemicals - this is why some animals mimic those who have bright coloration even if they aren’t toxic themselves (for example, non-toxic flatworms mimicking toxic nudibranchs). We’ve found some candidate chemicals in the disco clam’s bright tissue that may be the underlying “yuck” factor that helps them avoid being eaten.

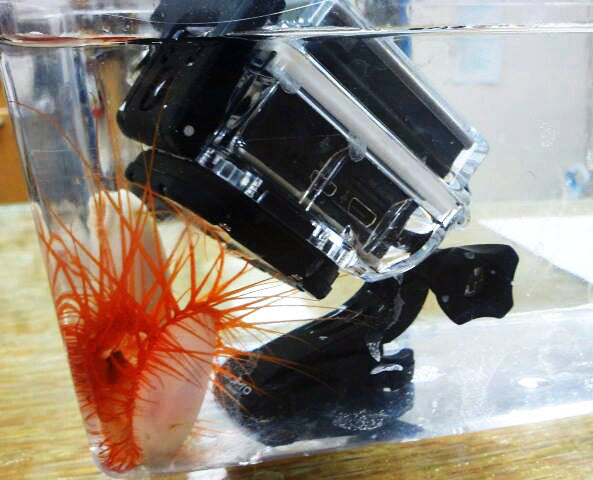

Once disco clams establish that something is not a threat (i.e. this GoPro is not planning to attack) they are actually quite curious. They use their tentacles as sensory organs, essentially smelling new objects and deciding whether they're something good to attach to.

We used peacock mantis shrimp as the experimental predator for the disco clams, and it turns out they do not like to eat the bright red mantle tissue that flashes. In fact, we filmed various unusual behaviors when predators encounter the disco clam mantle, including furious cleaning of mouthparts, repeated recoils from the clam, and the transition into a somewhat catatonic state (after which mating attempts occurred, further confirming the confusion on behalf of the predator). The bright red disco clam tissue appears to taste about as good as beets or brussel sprouts do to us. Apologies to those brave souls who genuinely enjoy brussel sprouts.

How to get the shot - Disco Clam edition

The toughest part about getting the ideal disco clam shot is finding the actual disco clam. Disco clams are relatively rare - there is usually one well-known disco clam that divers are taken to see over and over. If you look carefully for more, you can find them, but they’re often few and far between. Luckily, disco clams are sessile - which means they live in one spot and don’t move. This means that that the divemasters usually know exactly where to find one and will be more than happy to show you if you ask! Disco clams only live in the Indo-Pacific, but they have non-flashing cousins in the Caribbean - the rough and smooth file clam (Ctenoides scaber and Ctenoides mitis).

To get the shot, approach the disco clam slowly and be extremely careful not to stir up any substrate. Disco clams are filter feeders - meaning they use their gills to filter tiny food particles (plankton) out of the water. If there is too much sediment, they will close to avoid clogging up their gills. They will also close if you make any contact with their tentacles, so be sure to stay far enough away that you don’t touch even the most extended ones. When you’re finished, be wary of the photographer behind you, and make sure not to kick up anything as you leave. They’re often inside small caves (to find them, I usually say look for a big hole, then look for smaller holes, then look for really small holes), so they’re sometimes in confined spaces.

The real trick on how to get the ultimate disco clam shot is to switch your camera to video mode. Even the best shot of the mantle (with the reflective side exposed) doesn’t hold a candle to a video of the flashing. Another trick I use is to turn off my dive torch and let my eyes acclimate to the ambient light. You’ll be surprised at how vivid their flashing is without the extra light - in fact, the reflective spheres in their tissue that create the flashing are ideally sized and spaced to reflect blue light - which is most prevalent in the ocean (whereas dive lights restore red and the other colors that have already been lost as you dive deeper). After all, the fish, octopuses, and crustaceans that see the disco clam flashing are just using the ambient light available, they don’t have dive lights (well, aside from cheeky octopuses, which have likely stolen a lot of dive lights from scuba divers).

Disco clams like small crevices or holes in the reef. Often, they will grow to fit the hole, creating strange shapes, and may actually become larger than the opening so that they couldn’t swim out even if they wanted to. (Yes, they can swim, it’s not pretty - but it gets them from A to B (through X and other random letters). I’ve often found disco clams inside holes made by other boring clams (not that they’re a bore, but rather they bore into the rock or wood to create nice round holes. At the spot I found the most disco clams ever (>100), which I named the “disco clam cradle of life”, I even found new disco clams living inside the shells of deceased disco clams that were there before them.

Disco clams are broadcast spawners, meaning they simultaneously release eggs and sperm into the water (timed with the full moon) that mix and float around until they are large enough to settle on the bottom and start looking for a hole to live in. This float time, called a pelagic larval stage, is very important to development, as very few gametes survive to become disco clams. This life stage makes it impossible to raise disco clams in captivity, so any disco clams that are sold for aquaria are taken out of the ocean when they’re already full grown adults. They do not survive well in aquaria, and are not a sustainable addition to a home tank. Instead, consider species that are tank raised - aquarists are getting better and better at learning how to raise new species all the time.

Another close-up of the tiny eyes that line the mantle. The eyes can't produce images (they can't actually see you) but they are sensitive to both shadows and motion, which help them speed up their flash rate when they know a potential predator is nearby.

One amazing thing about disco clams is that they have about 40 tiny eyes along their mantle. They can’t see an image of you, but they can sense your shadow as well as your movement. When they see you, they will increase their flash rate (in the lab, it doubled), as they likely think you are a predator. We also saw an increase in flash rate when we added food to their water (think of Pavlov’s bell or the smell of freshly baked bread!). When you go to photograph or film them, check to see if you can see an increase in the flash rate as you approach. As they’re usually in small holes, you may want to detach a light to get it at just the right angle to illuminate all of the clam.

When people think about clams in general, they usually beeline to clam chowder. Bivalves in general are probably best known for the many dishes they provide - oysters in the half shell, seared scallops, and mussels in white wine, just to name a few. If you are a seafood-eating diver, you can be sure you’re always eating with the ocean’s health in mind by using the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Guide - they even have printable wallet-sized guides based on where you live. Luckily for bivalve-lovers, most clams are a good choice, with the exception of those collected using mechanized dredges and geoducks. Similarly, most scallops are a good choice with the exception of those that are collected with towed dredges. Mussels and oysters are a little more tricky, as a few types are not the best choice. If your favorite seafood restaurant can’t tell you where your seafood is coming from and how it was collected, perhaps it’s time for them to hear from their scuba-loving customers.

Giant clams are almost always open during the day as their zooxanthellae need access to sunlight to produce energy, and they are filtering water through their gills to get food. They typically close when they sense the shadow of a diver. This giant clam on the Wakatobi reef is really only about 6 inches across, but the fisheye lens is barely an inch away so he fills the frame. This is classic close focus wide angle photography. Photo by Ambassador Steve Miller

Bivalves are also known as pearl-makers, but aside from jewelry-making machines and edible aphrodisiacs, bivalves are actually a fascinating group of animals. They can be amazingly colorful, such as giant clams and thorny oysters - which surprisingly, use their thorns not as physical protection, but to attract epibionts (other small animals that live on top of an animal) to camouflage themselves. Hopefully this article instilled a new appreciation for bivalves, and the next time you are diving and see an interesting small crevice - check it out, as there may be a disco clam hiding inside. The best part about finding one may be getting to do the accompanying disco hand signal while channeling your inner John Travolta underwater.

Ambassador Lindsey Dougherty is an avid underwater photographer, and recently joined the Elysium Epic Expedition where she was the principal scientist for coral. Lindsey’s love of photography stems from her background in animal behavior - she received her PhD from the University of California Berkeley in 2016 on the flashing “disco” clam, and did the majority of her research throughout Indonesia. Her research has been featured in over 50 new stories, including the New York Times, CNN, the Discovery Channel, and National Geographic. She continued her research in Micronesia during her post-doc at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she teaches tropical marine ecology. Read more...

Ambassador Lindsey Dougherty is an avid underwater photographer, and recently joined the Elysium Epic Expedition where she was the principal scientist for coral. Lindsey’s love of photography stems from her background in animal behavior - she received her PhD from the University of California Berkeley in 2016 on the flashing “disco” clam, and did the majority of her research throughout Indonesia. Her research has been featured in over 50 new stories, including the New York Times, CNN, the Discovery Channel, and National Geographic. She continued her research in Micronesia during her post-doc at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she teaches tropical marine ecology. Read more...

Additional Reading

Capturing the Elusive Mouth Brooding Jawfish

An Insiders Guide to Diving Wakatobi Resort Indonesia

Close Focus Wide Angle In Depth

![Jenna Martin's TEDx on Becoming an Underwater Portrait Photographer [VIDEO]](http://www.ikelite.com/cdn/shop/articles/jenna-martin-tedx_underwater-portraiture.jpg?v=1645898040&width=2000)

![Creature Feature: Scaly-Tailed Mantis Shrimp [VIDEO]](http://www.ikelite.com/cdn/shop/articles/andrew-raak-mantis-shrimp_94754176-7954-412a-9f20-91d25ce4ab60.jpg?v=1645897544&width=2000)