By David Fleetham

All images © David Fleetham

It was Monday, the 4th of May, 1789. Captain Bligh and his seventeen loyal men had been on their 23-foot vessel for just one week and they had already lost one man to the natives after landing at Tofua, an island referred to by Captain Cook as “The Friendly Islands”. It turns out that this was an optimistic designation bestowed on the islands in hopes of it being true. They had entered Fiji just North of Yagasa and were now in the Yasawas. Reports of cannibalism were well documented in the islands of Fiji and the two canoes in hot pursuit did not sit well with the men who were sweating profusely as they pulled at the oars. Still heavily loaded with supplies generously dropped from the mutineers on the Bounty, water sloshed over the low gunnels of their lifeboat and one man bailed with a small wooden bucket as they slowly increased the distance between themselves and the enthusiastic Fijians. By sunset the canoes could no longer be observed.

For me it had been just two days aboard the Nai’a and here I was gazing out at the same fragment of ocean, now referred to as The Bligh Water. William Bligh went on to complete what is, to this day, called one of the most remarkable navigation feats in all of nautical history. He traveled some 3600 miles with a quadrant and a pocket watch to the only documented safe port on Timor. It took six weeks at sea and he arrived without loosing another man. I, on the other hand, had just finished a delightful bowl of ice cream topped with a warm brownie and was contemplating a wide angle lens or macro for the next dive.

My trip had begun from Nai’a’s homeport of Lautoka, a short ride from Fiji’s main airport in Nadi. Our first dive was a liveaboard's typical “check out” dive. This first submersion was for divers who had not been in the water for some time to get reacquainted with their equipment and discern the appropriate number of pounds for their weight belt. As explained by our dive guide, Soma Reef with its mix of sand and silt bottom, peppered with small coral heads and poor visibility was not typical. Having been to Fiji many times, I considered omitting this dive all together, but decided to check things out with a 100mm macro lens and macro mate. This combination allows me to shoot a tiny space not much bigger than your baby fingernail. With this set-up I do not cover much distance on a dive allowing me to scrutinized the reef for microscopic creatures one might customarily disregard.

As I investigated the surface of a blue sea star, Linckia laevigata, I caught the movement of tiny white dots. Picking up the five-armed invertebrate these same dots scooted around to the underside. I fired off a series of shots attempting to follow the tiny lice around the sea star. After downloading the images I still had to zoom in to really see what I had. Irwin Filius, our dive leader with several years experience in Indonesia before arriving in Fiji, had never seen these before and as the days went by I realized how extraordinary this was. Irwin showed me tiny shrimp and goby combinations as well as rare and endemic species I would never have found without his expertise.

It was not tiny creatures that brought me to Fiji again. I was looking for the iconic image from a country known for fantastic colorful wide-angle reef scenes. It seems that no mater where you go in Fiji there is always one dive site that is so jam packed with soft coral it is named with this in mind. So I was eager to see what Coral Corner had to offer.

It was early in our trip and so memorable that I decided to dive it a second time and then we stopped at it again on our way back. With colorful coral comes what some divers dread; current. I’m talking sideways exhalation bubble swirling current. This current is required to bring nutrient rich, deep-water upwellings to feed such a density of animals. So for me, current is my friend. When it is ripping is when all the soft corals are open and the reefs finned residents are in mid- water in a feeding frenzy. Thousands of schooling anthias pluck passing morsels and then suddenly, as if of one mind, dart back to the reef as several large jacks zip by. Further out from the reef several grey reef sharks hang motionless in the current, tail fins barely moving to maintain their position.

Days on the Nai’a began early in the morning. My iPhone would sing me awake at 6 AM and upstairs in the galley I would make myself a cup of tea and sample the various baked goods set out on the table. This was known as “First Breakfast”. From here it was out onto the dive deck for an explanation of where we were and what we could anticipate underwater. A diagram of the reef was sketched out on the white board as I pulled on my still damp wetsuit. Forward of here was a room set aside for only cameras. There was an abundance of carpeted workbench space that stretched from port to starboard and several tiers of shelves underneath with outlets for charging 110 and 220-volt gizmos. I did a last inspection of my rig and placed it on the floor in front of the rinse tank. From here it magically ended up on my dive boat along with my tank and equipment.

It was 7:30 by the time I gathered my mask and fins and stepped onto our skiff accompanied by my fellow passengers. The Nai’a has two custom made hard bottom inflatable’s to transport us over to the dive sites while she stays anchored close by. The other inflatable was off to a site named Mellow Yellow.

At the boat captain’s count of three, the entire boat does a back roll into the Bligh Water and the captain handed me my camera rig when I surfaced. The reef came close to breaking the surface and then dropped as a sheer wall to 40 to 60 feet where it then became a sloping bottom interspersed with coral heads that continued down hundreds of feet.

We had dropped in well off the wall and the current carried us toward it as we descended. The closer you got to the wall the greater the current and the greater the density of life. I had to repetitively kick back out from the wall and then shoot drifting into it. I kept thinking I had seen the best of the best, but as I drifted further I repeatedly found more and more breath taking combinations until I had completely deplete my strobes. With the picture taking done I continued to drift along the wall. Not being able to shoot made the end of my dive a frustrating experience and I vowed to get back to this same dive site again to capture what I was seeing.

Back on the Nai’a, under a hot shower, peeling out of my 3mm wetsuit I wondered if I should have brought my 5mm suit. Fiji waters can be just in the mid to high 70’s, which can bring on a chill towards the end of a 60 or 70 minute dive. Warmed by the shower, I dried off with my deck towel and then dropped it down a hatch in the camera room. The same towel would be dry, folded and back on deck at the end of the next dive. By this time my camera had been placed in the camera-only rinse tank and I retrieved it, dried it off and swapped the dead batteries for the two that had been sitting on my charger. Then darting through the salon area, down the stairs to my cabin I changed into some dry clothes. Time for second breakfast.

Each morning the galley crew would put out a menu for the day with several choices for each meal throughout the day. I had checked eggs Benedict and sure enough, one minute after I grabbed my juice and sat down, a steaming plate covered in my favorite yellow sauce was placed in front of me.

After breakfast I spent some more time in the camera room making sure my rig was ready for the next dive and then joined the rest of the group in the salon to watch a video from the previous day. This bit of sitting around was short lived when the bell rang to gather for the next dive briefing. I had switched skiffs in order to repeat my first dive and skip Mellow Yellow, despite the favorable ranting's of my fellow passengers who loved the dive. I knew what I had missed shooting on that first dive and so after dropping everyone else, I put in half way through the dive so I could shoot what I had seen after my strobes batteries had been depleted. I was moving slowly and it was no time before I was joined by the rest of the group who all gave me big OK signs in approval of my favorite site.

Completing five dives each day with a working camera can be a daunting task and one has to keep their eye on the clock. With strobe batteries switched and the card from my camera downloading onto my Mac, I sat down at noon for lunch to an old tune by Crowed House playing from someone’s iPod on the boat sound system. After lunch Irwin presented a video chapter from a series made by a previous photo pro who worked for several years on the Nai’a. Today’s was on creatures that worked in partnership underwater. He turned down the sound and narrated while we watched a shrimp excavate a burrow in the rubble as two gobies carefully surveyed the area for a sign of danger. I took note of the upcoming dive sites where we were likely to find these same species. Irwin was a wealth of knowledge that I mined for my entire time on the Nai’a. I made sure to catch these mid-day classes after each lunch.

The afternoon brought two more dives, with a snack in between, at a site now called Mount Mutiny. This is a circular pinnacle, perhaps three or four hundred feet across, that drops hundreds of feet on all sides and is cut with canyons that snake their way towards its interior. I dove this same site twenty years ago when it was named Hi-8, after a form of videotape from the time. Now out dated, the dive had been renamed, but I still remembered the sheer walls, colorful soft corals and variety of anthias fish at the different depths.

Lasagna, grilled asparagus and salad awaited me at 6:00 PM. While most of my fellow divers poured glasses of red wine to accompany their meal, I declined along with only one other passenger. It seems we were the only two who were night diving. This was bewildering for me. I would sacrifice a day dive if I had to, in order to night dive. The turnover of creatures on the reef at night is one of my favorite times. The day species are sleeping. Parrotfish are tucked into crevices, surrounded by a mucus bubble they secrete. Mollusks are out and moving about along with crustaceans that are completely hidden to divers during the day. I did pull out my 3mm hooded vest to wear under my wetsuit and was pleased I had included it. As much as I am fond of night diving, my bed was just as appealing by the time I showered and my head hit the pillow at 10:30.

Five dive days are long and can be arduous, but when will I see reefs like this again? I did not miss a single dive. Irwin pointed out that the schedule can be confusing and when in doubt, you should just run your fingers through your hair. If it is wet, then it is time to eat. If your hair is dry, then it is time to dive. Our ten days went by quickly as we meandered from the Bligh Water over to the Koro Sea. Most of the traveling was done at night, so we would find ourselves at new locations each morning. Wakaya, Vatu-I-Ra, Namena, Makogai, (pronounced “muck on guy”), Gau (pronounced “now”). Fijian pronunciation can be challenging at times. I did better with the dive site names. White Wall, Manta Rock, Jim’s Alley, Anthias Alley, Nigali Passage, Two Thumbs Up, North Save A Tack, Cat’s Meow, Humann Nature (after Paul Humann), Grand Central, The Arch, Kansas, Fantasy and Howard’s Diner, named after Howard Hall who shot an Imax film here. The list is longer. These ones are particularly memorable for some of my favorite images.

Not every day involved five dives. One afternoon we toured an isolated local village and were treated to a Fijian dance and Kava ceremony. Kava is a root that is transformed into a traditional drink in many parts of the South Pacific and is exceptionally significant in Fijian culture where it is also known as Yaqona. It has the color and consistency of diluted mud but is slightly more pleasant than what one would imagine diluted mud might taste like. The drink is served out of a large wooden bowl carved to have four legs. Guests generally are asked to sit with the village chief and the higher-ranking residents with the Kava at the center of the circle. The drink is served in half a coconut shell, one serving at a time. When offered you would clap once, consume the contents of the shell and then clap again three times. This is then repeated throughout the room for several hours until all the Kava is gone. The drink acts as a mild sedative while still leaving ones thoughts relatively clear, although slightly numb lips and tongue have been reported. It is used to promote storytelling, socializing and appreciation, and was certainly effective for our afternoon that quickly turned into a dazzling sunset as we returned to the Nai’a.

Several months and several e-mails after returning from Fiji I narrowed down the identity of the tiny specks on the sea star. I started with my good friend John Hoover, author of several marine ID books here in Hawaii. He sent me to Dr. A. J. Bruce at the Queensland Museum in Australia who took an educated guess but suggested a contact at the Friday Harbor Laboratories, part of the University of Washington. From here I got to a Professor in the Department of Life Sciences at the Natural History Museum in London, England who seems to know more than most on the miniature organisms and wrote the following.

"It is snowing in London and I have been dealing with my daily mountain of boring emails.....until yours. A nice surprise to see such a beautiful animal! Yes these are symbiotic copepods - and the females are carrying the white paired egg sacs. Several families utilize sea stars as hosts and I can't tell which family your beast belongs to from the photos. However, from the dorso-ventrally flattened body form and general habitus - the main candidate is the Lichomolgidae (a few genera of which occur on sea stars). For animals this size, we need to dissect and count the segments and spines on the legs etc.

"A very quick check reveals that several species of the lichomolgid genus Stellicola have been recorded from Linckia laevigata: e.g. S. flexilis Humes, 1976 from the Moluccas, S.illgi Humes & Stock, 1973 (also Moluccas), S. novaecaledoniae Humes, 1976 (New Caledonia), etc. So if you ever obtain material - I would start the process of trying to identify this copepod by looking at the lichomologids and at Stellicola in particular."

So now I have an excuse to go back out on the Nai’a. This was not my first adventure to Fiji and what better reason to return than to discover a new species! Not that I need an excuse. Beyond the diving, the Fijian culture is one of the most welcoming you can encounter in dive travels. If I had one complaint about being on a liveaboard vessel it would be that it limits your access to such wonderful people. So after my time on the Nai’a, I then spent a week in the Beqa Lagoon area on the same main island of Viti Levu. But that is another story for another day.

Ambassador David Fleetham left his hometown of Vancouver, Canada, for Maui in 1986 and never looked back. He earned his USCG Captain's license while working in various dive charter businesses, shooting, and submitting his photos to magazines and businesses. One of the most prolific underwater photographers of his time, David now has galleries and agents in over 50 countries that reproduce his images thousands of times each year. Read more...

Ambassador David Fleetham left his hometown of Vancouver, Canada, for Maui in 1986 and never looked back. He earned his USCG Captain's license while working in various dive charter businesses, shooting, and submitting his photos to magazines and businesses. One of the most prolific underwater photographers of his time, David now has galleries and agents in over 50 countries that reproduce his images thousands of times each year. Read more...

Want the easy way to improve your underwater photography? Sign up for our weekly newsletter for articles and videos directly in your inbox every Friday:

Additional Reading

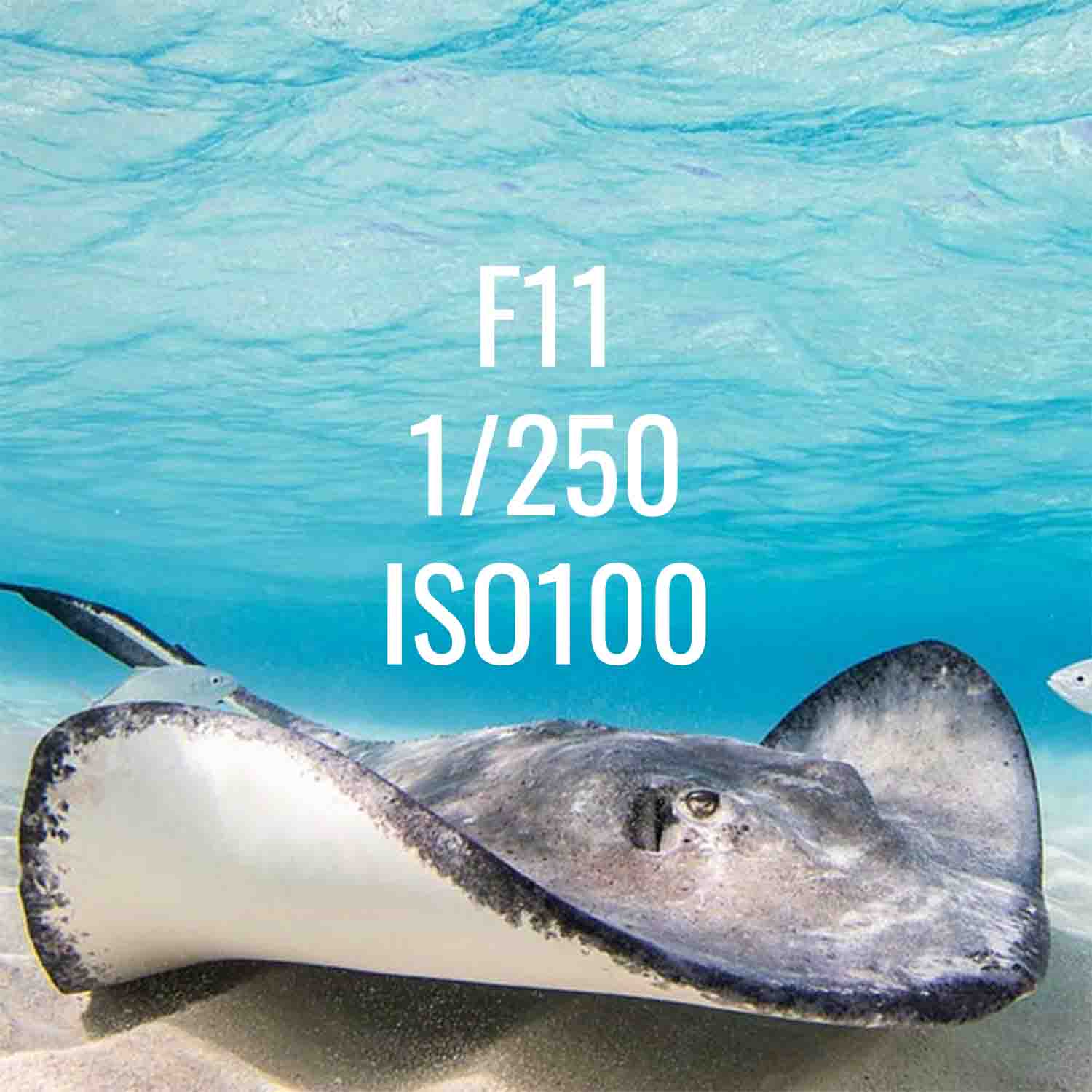

Tropical Reef Underwater Camera Settings

An Insider's Guide to Diving Yap, Micronesia

Mandarinfish Underwater Camera Settings and Technique

Transitioning to Canon Full Frame Mirrorless | Canon EOS R Underwater Photos

David Fleetham's Tips on Housing Assembly & Maintenance [VIDEO]

![Diving and Visiting Catalina Island [VIDEO]](http://www.ikelite.com/cdn/shop/articles/Catalina_Cover.jpg?v=1654549713&width=2000)