By Adam Hill

In early 2019, I was on a mission to gather support to help save the ocean. Why? Because I was about to join an 80 day expedition supporting ocean advocate, adventurer and long-distance swimmer Ben Lecomte as he took on 300nm of the most polluted water on our planet; The great pacific garbage patch. The aim was to expose the truth about ‘the patch’ as he in partnership with a plethora of scientific institutions undertook a scientifically coordinated swim through its worst affected areas.

I’m a doctor from the UK that has grown up surfing the Cornish coast, and in later years capturing its many faces through a lens. I like many however have languished over years of feeling growing sense of frustration, that our beaches and the worlds oceans are suffering at our hands. No matter how many beach cleans I participated in or plastic bags and wrappers I stuffed into my wetsuit sleeve, the tide of plastic was growing. A chance encounter with a post online however saw me propelled to the other side of the world to join a quest to find and document the worst hit area on our planet: The great pacific garbage patch.

Ben Lecomte swimming in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge off the coast of San Francisco, California. This portion of the expedition left Honolulu on June 8, 2019, and the journey to San Francisco took about 80 days.

The expedition was to help support Ben Lecomte (Transatlantic swimmer) in his quest to build on an earlier attempt to swim the pacific. Ben Lecomte is a man possessed with a love of the ocean and a need to just keep swimming, sadly he has lived through a time where the ocean he loves has now become home to our worlds plastic waste. During 2018 Ben swam from Japan to Hawaii, battling cyclones, technical difficulties, strong currents and a growing tide of plastic. The crew arrived on Hawaii, tired and bereft of an ocean crossing, but moved to action by the enormity of the plastic pollution seen in our once pristine oceans.

Adam left his normal life in the UK to join the expedition as a volunteer doctor and photographer.

The current expedition is the culmination of individuals and organizations co-ordinating with scientific institutions to enable Ben to swim in a manner thats no longer a personal quest to cross an ocean, but that lends a voice to an issue that affects us all while being legitimized by well guided citizen science.

The crew sorts through the plastic soup they bring up in large buckets. Though they don't make as much visual impact, microplastics are among the most threatening environmental disasters in the oceans right now. These plastics end up in the digestive systems of much of the marine life. Some estimates say that more than 90% of seabirds have small plastic pieces in their guts.

The trip spanned 80 days at sea on a 67ft challenger class steel monohull vessel, designed originally for the BT global challenger around the world yacht race. Now repurposed as a swimming and research support vessel, gone are the days of speedy crossings, as now a more sedate pace is required. Bens swimming allowed us to tow nets, quantify plastic concentrations, take samples, collect photographic evidence and most importantly gain an underwater view at a pace not often observed. The path is plotted via careful consideration of satellite information that addresses wind speeds, currents, planktonic upwellings, and converging pressure systems.

The great pacific garbage patch is a vast area that is unfathomable in imagination, so its often referred to being ‘twice the size of Texas’ and due to a persistent high pressure zone, in the North Pacific, is an area of calm where the worlds waste congregates with the aid of localized currents.

Fishing doesn't just harm the unlucky fish that got caught. According to Sea Shepherd Society, approximately 46% of the ocean plastic in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is made up of fishing nets.

Everyone one of the crew has volunteered their time, money, ‘know how’ and equipment, this isn’t glamorous, and it's not a holiday. There are 10 people sharing a living space smaller than some peoples front rooms. We live off of canned food, and ration packs, and have limited fresh water, we run off renewables and when someone is cooking the whole boat becomes a sauna. There is no internet, we have limited data to send out scientific information and a few choice shots to help our land based media team an opportunity to help tell our story.

The areas of the ocean where we have seen the largest concentrations of plastic has also seen us see our most prolific contacts with marine life. In conjunction with the Smithsonian and NOAA we have documented all our exchanges with plastic and marine life, with myself and 2 other photographers delving into the deep blue on a daily basis. Capturing this exchange between our marine cousins and the plastic they now swim through has been challenging. The plastic is often degraded and fractured into a fragments mm in size. Its a like a soup interspersed with larger less frequent pieces still in the process of breaking down. The larger pieces are easy to capture and almost certainly have a hitchhiking crab clinging possessively to it. A photographers aim is to capture what we’ve seen and convey it in medium that encompasses not just the objective but the subjective; the feel of it.

Confused little crabs should be making their homes in shells, but due to the proliferation of pollution they tuck themselves in all manners of discarded plastic waste instead.

The plastic soup that is increasing in concentration year on year isn’t a subject matter i’ve had to cover before, and it evades capture, the pictures just look foggy or confusingly similar to plankton and other lower order trophic feeders. This is the problem; how do you representatively convey the state of the ocean, and its alarming decline when you can’t picture the problem. There isn’t a conveniently placed plastic bag on each dolphin swimming by, but you may have just see both individually occupying the same space, the scene is set but not all the actors are on the stage at the same time.

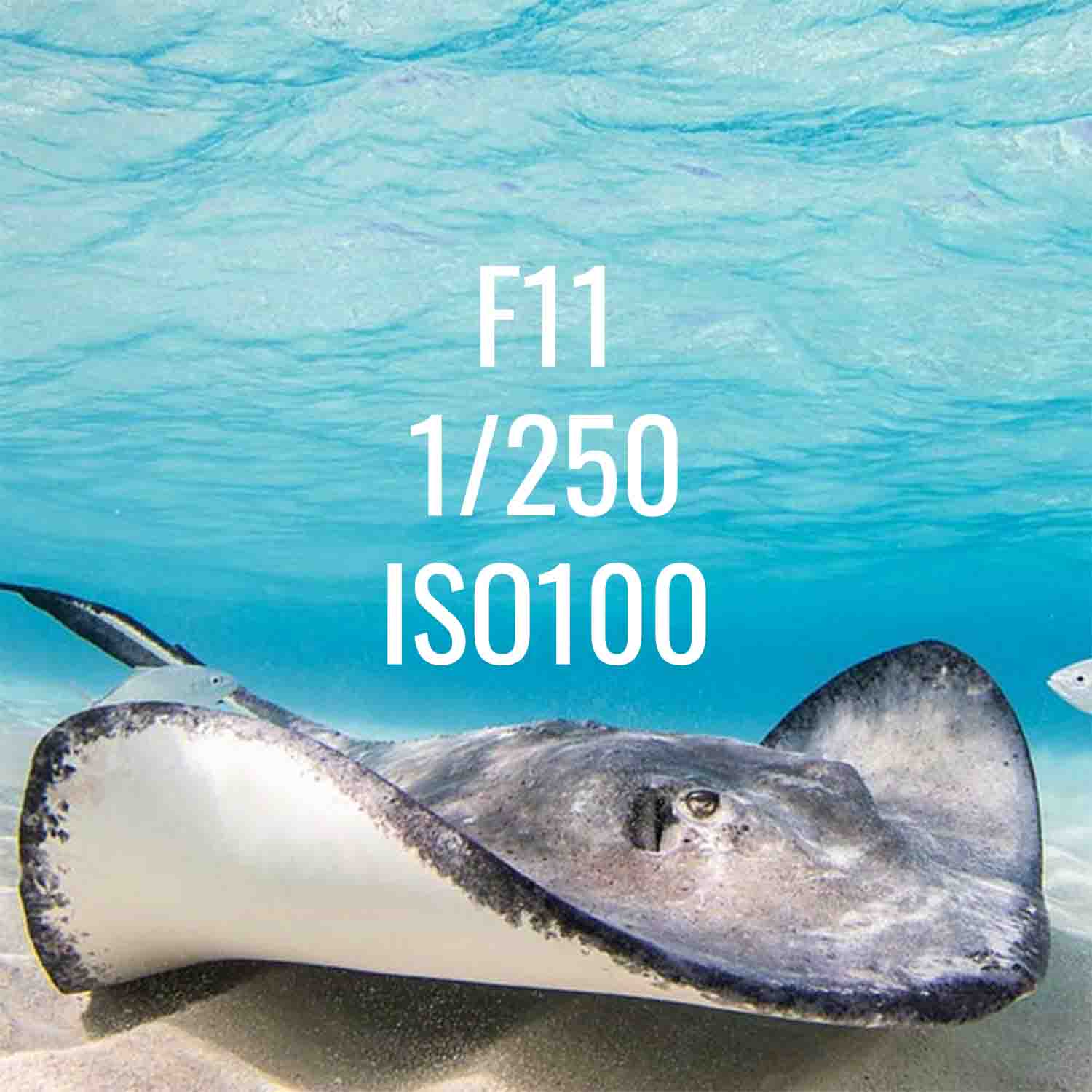

The Ikelite housing we used with the Sony A7RII's allowed us to adjust and modify the settings on the go, to try and capture not just the marine life but the plastic. The differing depth of field required meant a lot of adjustment not just with focal lengths but with the auto focus alignments. The ability to modify these on the fly underwater with whales and dolphins coming in and out of shot with seconds to spare was essential.

Adam was able to capture a some unspoiled moments of beauty as dolphins and whales swam by to check them out. But that's not all good news. Presence of whales and dolphins in the Pacific Garbage Patch may mean that they are feeding on the waste and likely getting trapped in it.

Maintenance of the equipment was our next hurdle, we had cameras during the voyage turn almost entirely to rust despite fresh water rinses, and sealed environments. The water housing units we had were no different needing to be rinsed, dried and carefully sealed away, and even with such precautions 3 months at sea takes its toll. The housing provided by Ikelite was a blessing with little freshwater available the sparse exterior metal elements were easily cared for within my meager water rations.

We're back on land now, all of us different from what we experienced, all changed in ways we are still discovering. How do we as a society embrace the knowledge that our ecosystems are failing and find sustainable and environmentally paths forward? I know our venture was a drop in the ocean, amongst the growing tide of people calling out for change but more needs to be done.

Thanks to Ikelite I was not only able to capture photography that has gone on to be used across the world to highlight the growing plight of oceanic plastic, but a reaffirmation that their are companies out there that understand the problems we are facing and are willing to stand out and support causes such as ours; from me and the team of the Vortex swim I thank you.

The longterm solution to this problem is to reduce the generation of new waste. Governments, industries, and individuals must make the decision to look for more sustainable options and better regulate the down-cycling of plastic materials.

All images copyright © 2019 Ben Lecomte

Adam Hill is a passionate ocean advocate, underwater photographer and expedition doctor. Attending medical school on the welsh coast, strengthened an existing desire to explore the marine world further. He received degrees in Medicine and Surgery from Swansea University (UK) with a specialism in remote and rural medicine. When not at work Adam can be found supporting local marine conservation charities, searching for hidden waves with a surfboard or a camera and continually pursuing a more sustainable lifestyle. Check out more of his photography at www.adamhillphotography.com and on Instagram @osleston

Adam Hill is a passionate ocean advocate, underwater photographer and expedition doctor. Attending medical school on the welsh coast, strengthened an existing desire to explore the marine world further. He received degrees in Medicine and Surgery from Swansea University (UK) with a specialism in remote and rural medicine. When not at work Adam can be found supporting local marine conservation charities, searching for hidden waves with a surfboard or a camera and continually pursuing a more sustainable lifestyle. Check out more of his photography at www.adamhillphotography.com and on Instagram @osleston

Additional Reading

Every Little Stretch of Coast is Dying, We Need to Act Now!

Protecting the Natural Resources of the Bahamas with Bahamas Girl

Coral Reef Restoration Program in Bonaire

![Behind the Scenes // Scuba Diving Open Water Certification [VIDEO]](http://www.ikelite.com/cdn/shop/articles/dive-cert-1-cover.jpg?v=1688680622&width=2000)